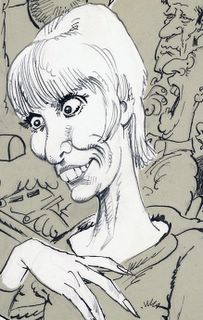

Robert Heindel died this year. He was only 67 years old, with many great years of painting still ahead of him, but he had been ill and surely knew the end was near. I was fortunate to talk with him a few months before he passed away, and hear his conclusions about illustration as he approached the end of his career.

Heindel was born in Akron Ohio and, with no art training except a correspondence class, worked his way up from tire advertisements in Ohio to car illustrations in Detroit to magazine illustrations in New York, where he became close friends with Bernie Fuchs and Mark English. From there, he single handedly carved out his own specialized niche painting beautiful images of dancers. He made an excellent living selling prints and originals of his paintings in galleries around the world and over the internet. This career path was a remarkable accomplishment. Heindel knew what he wanted to do and invented a career to permit him to do it. His example should be an inspiration to others looking for a career in the visual arts.

The following quotes are from my conversation with Heindel this summer:

"The business of illustration is literally nonexistent today.... When Bernie Fuchs and I did what we did, it was a different world. We had to make a lot of hard decisions as things changed. Where do kids starting out today take their talent if they want to do what we did? I would say they’re fucked. There is nothing for them. They can’t follow the path that Bernie and I followed any longer. And our society is pretty unforgiving for those who make the wrong judgments.

"You do what you have to do to have the life you want. You get up one morning, you start to feel oppressed by what you do. You want more freedom. I worked it out so I can stay up here in the woods in Connecticut. I have three business partners that run a big business around the world. I don’t take assignments anymore, I do what I want to do when I want to do it....All of this could only get done with technology [like the internet, digital imaging and telecommunications]."

"When I pushed the boundaries it made my work harder to sell and drove my partners crazy. Now I don’t have the energy level I once did. You realize when you get to be my age that you aren’t really as good as you wanted to be. You have to confront the question, “how good am I? Why can’t I be better?” All I can tell you is that I keep knocking at the door."

"When you do really terrific work, you know that you’ve done it. You can tell. I know who I compare myself against, who I’ve been up against. And it starts all the way back with the cave paintings in France....You start out thinking your competition is the guy you want to get a job away from that day. Then you gradually realize that you are your competition. The job is your competition."

When I spoke with Heindel, I found him to be a profound, thoughtful, sensitive man who had clearly spent a great deal of time at his easel musing about life's big issues. He was also funny and irreverent. I'm sorry that I only met him at the end of his life, but I am proud to pass his pictures and his ideas on to the readers of this blog.